The Wisdom of Silliness

What does it mean to believe in fairy tales?

“My dear Lucy” writes C.S. Lewis in the dedication of his Narnia series to his goddaughter, “I wrote this story for you, but when I began it I had not realised that girls grow quicker than books. As a result you are already too old for fairy tales, and by the time it is printed and bound you will be older still. But someday you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again.”

We live in a world where people tend to be very worried about serious things like money, taxes and degrees and scoff at things like fairies and dragons, witches and spells, and angles and demons. What is a fairy tale to a man concerned about the election of a state he does not live in? What does a witch turning a prince into a frog matter to a woman concerned about a war in Eastern Europe as she sits somewhere in Canada?

Much of this is due to the “enlightenment” in which men laboured under the illusion that they were the very first people to ever use reason, even as they stood in the shade of magnificent cathedrals. The enlightenment incepted the idea that only that which is materially measured is real and everything else is simply...silliness.

However, modern man is in no place to denigrate fairy tales because he himself lives a life of money that magically appears, and disappears, in numbers on a screen. A million unseen characters exist to him on a glowing magic mirror in his hand. Modern man may touch this magic mirror in the correct ways and a pizza will appear at his door...or the police to arrest him. C.S. Lewis in Abolition of Man argues that there is actually little difference between technology and magic in that they are both material transactions to assert man’s will upon the world somehow. It is just that technology is understood by some laws of physics, whereas magic is not. To the majority of people, most modern technology is functionally just magic.

“It is the magician’s bargain: give up our soul, get power in return. But once our souls, that is, ourselves, have been given up, the power thus conferred will not belong to us. We shall in fact be the slaves and puppets of that to which we have given our souls.”

“There is something which unites magic and applied sciences while separating both from the ‘wisdom’ of earlier ages. For the wise men of the old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique. And both, in the practice of this technique are ready to do things hitherto regarded as disgusting and impious.”

(Excerpts from C.S. Lewis’ “Abolition of Man”)

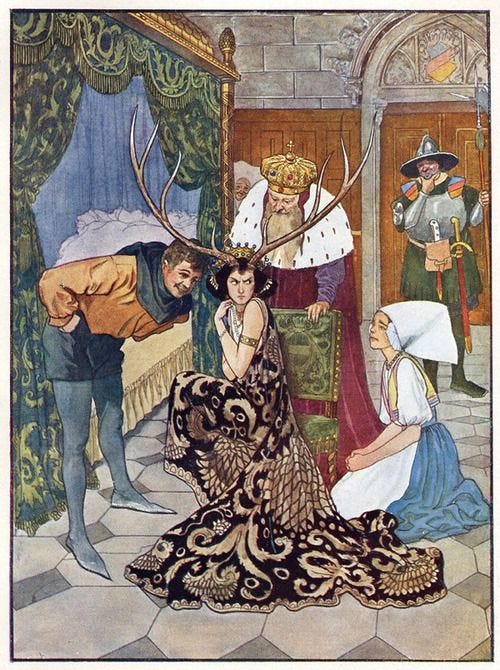

The magic of the fairy tale is created through language. A witch can turn a prince into a frog. A princess may find herself at night in a forest with trees that have precious rubies and sapphires hanging from their branches instead of fruit. A palace may be built upon a cloud and a flying horse will take you there if you are pure of heart. Each of these lovely images were created through words. Although words can be used to create horrible things as well. A law is a word that can turn a decent society into a police state, a dystopia. A judge may rule through words alone that a convicted murderer should be sent back out to the streets not once but fourteen times, where he will murder a girl on a train in cold blood as was the case of Iryna Zarutska. A policy maker may decide through words alone that money can be taken from people’s hard earned savings to fund foreign wars as is the case with the modern Britain. Modern man must be keenly aware of the power of words in his world to make, and to unmake.

When we say that we ought to “believe in fairy tales” it does not imply that we believe in the existence of flying horses or castles built on clouds. Believing in fairy tales is not a material belief in the things of the story, but rather a willingness to imagine that world and use it to understand the metaphysical ideas that pervade our own world.

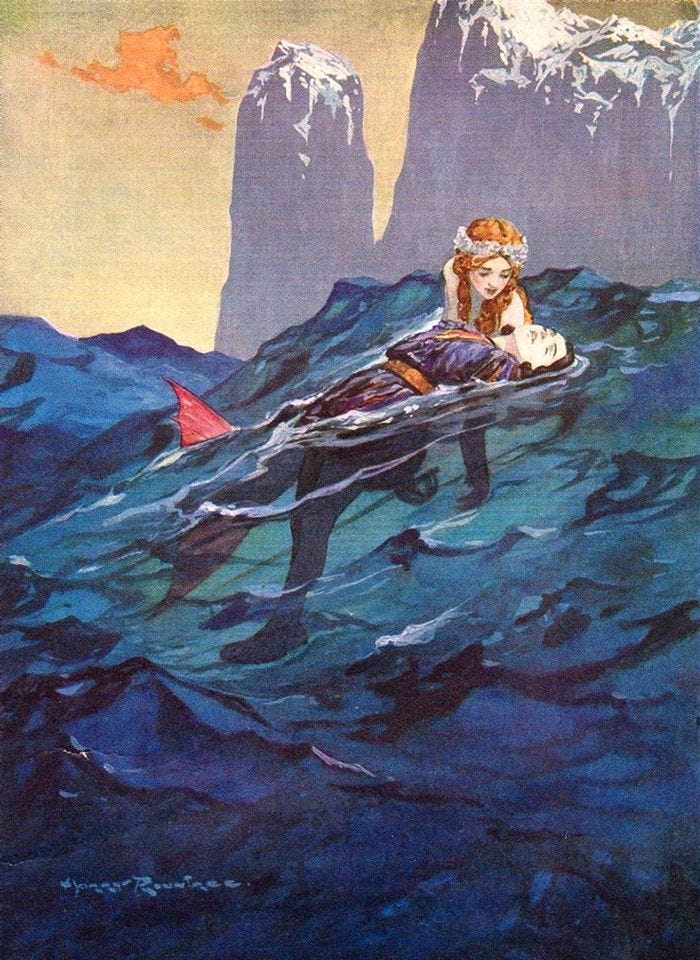

A fairy tale in which a mermaid becomes human in order that she may love a man and be a human woman with a human soul, reminds the reader of the immense privilege it is to be a human being already given this opportunity. As the mermaid dies at the end of the story because she tried to gain this advantage through witchcraft, which always demands a horrible blood sacrifice, the reader feels sympathy for the being that died to have what we were given as a birth-right. This is Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid”. Believing this fairy tale is not about believing that mermaids exist somewhere in the vast deep of the ocean, but rather about believing that love is so precious that a magical being might give up everything to attempt to have it. But the kind of people who look at the vast ocean and cannot imagine a mermaid somewhere in it swimming in its deep, are people who are a bit dead inside anyway. What if is the beginning of all dreams, and it is only those who have the imagination for mermaids and dragons who can also imagine building a machine that could help man fly, or a carriage that runs faster than 100 horses on its own. For all dreams begin as silliness and real fairy tales are the training of the mind in two things: the cultivation of silliness and the cultivation of a sense of morality and justice.

When we read The Snow Queen to little children, we may enchant them with tales of a the fairy that makes the frost on our windows in December, or a witch who can make flowers that make a little girl forget all her family and friends. Just as in The Little Mermaid, there are truths also in The Snow Queen which cannot be easily captured in a lesson for children to memorize as they may memorize the parts of a flower or the order of the planets in the solar system. The story of the Snow Queen is about an evil glass made by goblins that sometimes gets stuck in the eyes of human beings and when it does they are compelled to see the whole world as horrible. This makes them miserable and horrid people in turn. The truth of the Snow Queen is not that such a glass materially exists, but rather that the way we are used to seeing the world can impact the way that we live in it and that one’s psychological outlook on the world is powerful in shaping perception. Only a fairy tale can take such a complex metaphysical idea and put it in a way that even a four year old child can understand it and implement it in his life.

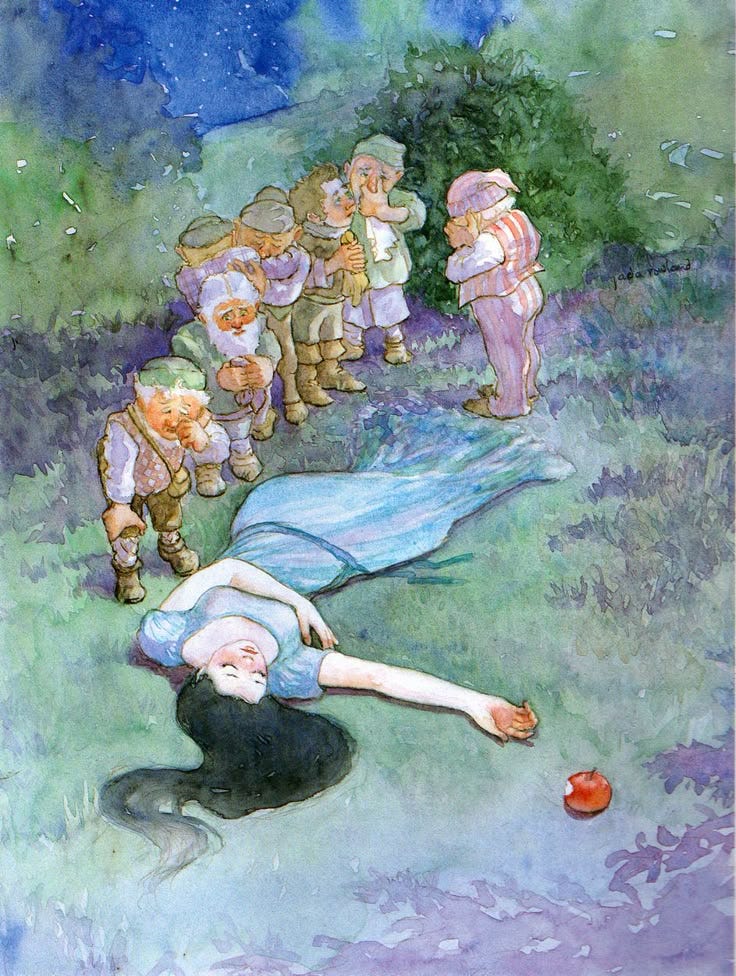

Of course, I am in danger now of being a utilitarian because I am so used to speaking with utilitarians in our rational world of returns-on-investment and key-performance-indicators. The main wisdom of fairy tales is their delight and silliness! Both children and old people have this wisdom in common which is that they actually enjoy their lives without attempting to measure the ROI of that enjoyment. However, there is a very big difference between mindless entertainment and true delight in art. On the one hand, someone watching the Kardashians or Love is Blind might be engaging in harmless “who cares!” fun as well. But this kind of fun is laced with poison: a glorification of immorality, injustice masked as liberation, and the destruction of our aesthetic sense. The main difference between art and entertainment is that art, even as it is enjoyed for its own sake, edifies and deepens our lives long after it is gone from view. Whereas entertainment can be quickly forgotten and if it is remembered, it is remembered to justify or normalize immorality.

Not all fairy tales are created equal. The fairy tales of Lang and Andersen are very different than those written by Grimm or Basile which tend to be far more vulgar and gruesome. And all of these differ greatly from the fairy tales of the Thousand and One Nights, which are not based in any Christian moral worldview but rather an Eastern one where deceit and mischief are rewarded rather than punished. But all of these fairy tales have something in common, which is that they begin the discussion of justice and morality with our children and with each other. When a boy succeeds in stealing a treasure and winning a princess with it, we can discuss whether what he did was right or wrong. We can enjoy the whimsy and fantasy of these fairy tales, so long as we have one far more important story to guide us on the truths of morality and life behind them all.

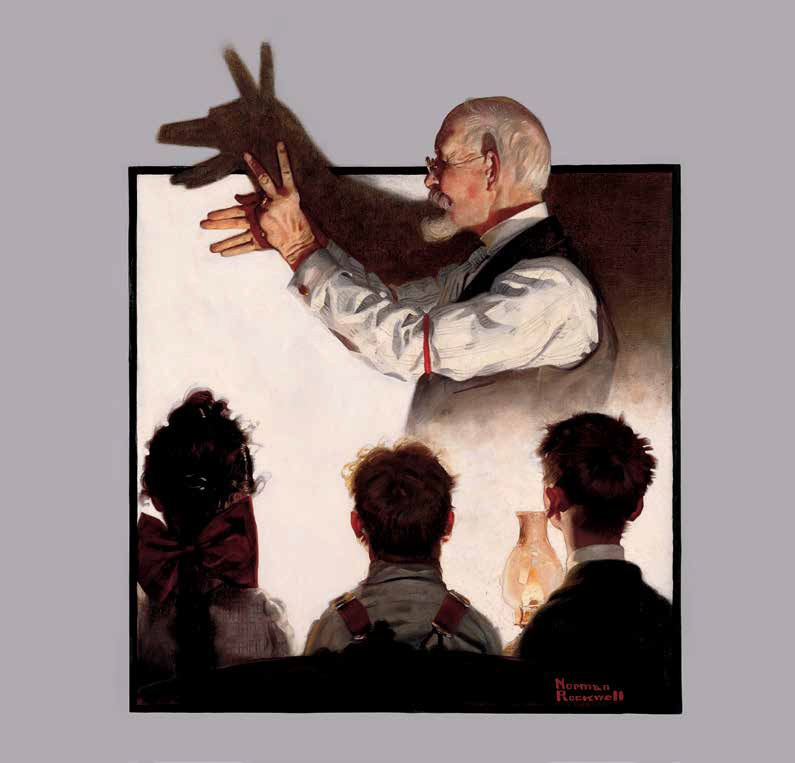

In his message to his goddaughter, Lewis describes a phenomenon of the older person recovering the wisdom of children as she ages. The wisdom of fairy tales is the ability to enjoy the fantastic world of silliness and whimsy, which is very difficult to do for adults who seem to be caught up in very important “work” all of the time. Perhaps this is one of the reasons we have children: so that they can stop us from forgetting about the joy of jumping in a puddle or singing out loud whenever we feel like it. Children and old people are masters of silliness because one is too young to care what others think too much, and the latter is too old for it. We adults in the middle, we are the ones stuck with the constant performance about our own importance and seriousness.

Go ahead, read a little fairy tale. Sure it will tell you ridiculous things like a little girl the size of a thumb can be born in the centre of a flower, or that a boy might climb into the land of giants on a bean plant. But the fairy tale will also help you think outside your own little box and exercise that muscle of imagination. Yes, it may or may not teach some morality, but fairy tales are, first and foremost, for fun, and the sort of fun that preserves your innocence and belief in the good, rather than indulges your vices.

Fairy tales are not lying to children because they never presume to be materially true. Rather, fairy tales are letting children imagine if. How horrible and stultified would the world become if people no longer had that ability.

“You cannot go on ‘seeing through’ things forever. The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it. It is good that the window should be transparent, because the street or garden beyond it is opaque. How if you saw through the garden too? If you see through everything, then everything is transparent. But a wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To ‘see through’ all things is at the same as to not see.”

- C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man

Thank you for reading my monthly free essay. I hope you enjoyed it!

Most people treat fairy tales like leftovers from a simpler age — something to outgrow. But you’re right: they form conscience more effectively than most sermons. The fact that silliness teaches children more about courage and evil than schoolbooks should embarrass our institutions. But maybe its because Im a cop, I dont see our dilution of fairy tales as a coincidence. institutions like Disney have purposely taken fairytales and stripped them of all moral teachings.

Fairy tales train the soul with beauty and danger — long before the world tries to flatten everything. I love how you’ve reclaimed silliness as a form of strength. We need more of this. More wonder. More play. More stories that make us brave.

In the Marines, the silliest men were also the toughest. When shit hit the fan, their spirit didnt diminish. Lack of silliness was a sign of stress taking over and ptsd setting in.

This was so fun to read. I read a book of Arabian nights to my kids several years ago and didn’t care of it at all, so I appreciated you mentioning the differences between types of fairy tales and the underlying morality.

Is there a particular edition you could recommend?